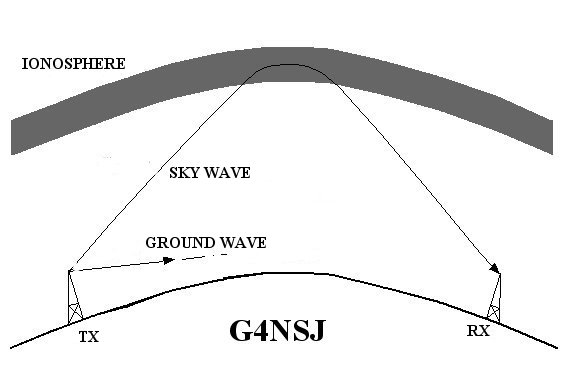

Forget about the D layer and the F layer and all that stuff for the moment. As far as we are concerned, the ionosphere is a kind of ceiling above the earth. We send out a radio signal and it hits the ionosphere. This signal is the SKY WAVE. Why is it called the sky wave? Because it goes up into the sky.

At certain frequencies, the ionosphere is like a mirror. It reflects our sky wave signal back to the Earth. Where the signal lands on the Earth depends on the angle at which the signal hits the ionosphere. Shine a torch into a mirror and move it about. The reflected beam moves depending on the angle of the torch.

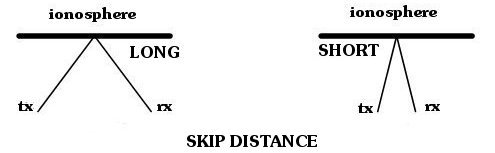

When people talk about SKIP, they mean the distance between the transmitter and the nearest point from the transmitter where the sky way returns to the Earth and can be received. In other words, the land over which the radio wave jumps is the skip distance. No sky wave signal will be received in this skip zone. Or, at least, very little.

You might hear someone saying that the skip is long on 40 metres. Or short, come to that. They mean that, during long skip conditions, inter-G working is poor or impossible, whereas the continental stations are romping in. During short skip conditions, inter-G working is great. But the continental stations have all but faded away. See the above diagram for long and short skip. Take a look at the diagram below and you’ll see the radio signal leaving the transmitter, bouncing off the ionosphere, and returning to the Earth. The ground wave is something we’ll come to in a minute.

RADIO WAVES

Arranging your aerial so that it fires the signal almost straight up to the ionosphere is called NVIS (near vertical incidence sky wave). The idea being that a station pretty close to the transmitter will be able to receive a good signal even if there’s a mountain in the way. The signal goes almost straight up, and down again, skipping over the mountain. This is all very well at certain frequencies such as five megs. However, at other frequencies, the sky wave will drive straight through the ionosphere and go out into space.

MUF (maximum useable frequency)

The maximum useable frequency is the highest frequency (at any time) at which radio waves bounce off the ionosphere. There are MUF charts available showing the maximum usable frequency over a period of time. These are useful if you have to keep in constant contact with a fixed station.

GROUND WAVES

The ground wave leaves the transmitting aerial and it travels along the ground. OK, not on the ground, exactly, but very close to it. This ground wave, which is slightly above the ground, gradually peters out with distance. The distance over which this occurs depends on the power of the transmitter, the aerial, the terrain.

Virtually all contacts made on top band, 160 metres, during the day are by ground wave. The same applies to medium wave stations heard during daylight hours. At night, signals on top band are able to bounce off the ionosphere and return to the Earth. This returning to the Earth is sometimes thousands of miles away from the transmitter site. The reason for this is that the ionosphere changes its characteristics between the hours of sunlight and darkness.

This is a good time to quash a myth. People talk about the sky wave and the ground wave. These aren’t separate waves. There aren’t separate ground and sky waves leaving the transmitting aerial. The aerial chucks out waves in all directions. The ones following the ground are called, ground waves. And the ones going skyward are called, sky waves.

So you’re sitting in your shack one evening listening to a station on top band. One minute the signal is very strong and, the next, it’s all but disappeared. This could be due to several reasons but, very often, the sky wave is reaching your aerial along with the ground wave and the two either cancel each other out or combine to make a strong signal. This depends on the phase relationship between the two signals and stuff like that.

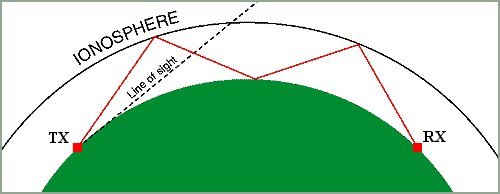

Back to the sky wave for a moment. We fire a signal up to the ionosphere and it’s reflected back to Earth. When it hits the Earth’s surface, it may bounce off and again return to the ionosphere. Up down, up down all the way around the world until it dies a death. One bounce off the ionosphere is great for getting from the UK to, say, Italy. But when working Australia, multiple hops are necessary. Take a look at the diagram below.

BOUNCING AROUND THE WORLD

You may hear echoes when listening to a distant station on 10 metres. This is the signal going around the world more than once, hitting your receiving aerial at intervals, the time delay between each hit causing the echo. As I said earlier, the TX aerial sends out radio waves in all directions and at all angles. So it’s not just a simple case of one wave going up down, up down. Also, depending on the angle at which waves hit the ionosphere, some will go straight though, some will be reflected, and some refracted.

Just a quick word about the height of aerials, particularly aerials for 160, 80 and 40 metres. We’ve talked about NVIS, firing the signal straight up, or as near as damn it. In fact, the majority of end fed wires and dipoles are NVIS aerials. Why? Because they are so low in comparison to the wavelengths concerned that they fire the signal skyward. The higher the aerial above ground, the lower the radiation angle.

Radiation angle? This is the angle at which the signal leaves the aerial. The signal is fired in all directions and at all angles, but there’s a concentration in certain directions and at certain angles. This concentration, or lobe, depends on many factors. One of the main factors is the aerial’s height above the ground. The higher the aerial, the lower the radiation angle. This is great for DX as the signal travels at a low angle for many miles before glancing off the ionosphere and returning at a low angle to the Earth.

For inter-G working, usually, the lower the aerial the better. This is because the signal is fired straight up and most of it rains down and splashes all over the UK. In fact, for NVIS work, aerials are sometimes laid on the ground. Yes, they still work!

More on propagation here.